About Keratoconus

Keratoconus (or conical cornea) is a disease that results in thinning of the central zone of the cornea, the front surface of the eye. As this progresses, normal eye pressure causes the round shape of the cornea to distort and an irregular cone-like bulge develops, resulting in significant visual impairment.

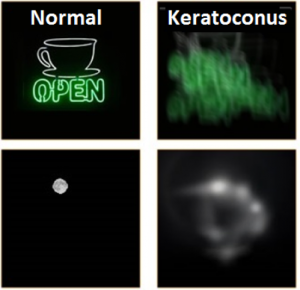

The poor quality vision occurs primarily from irregular astigmatism and distortion that results in the image focussing at multiple points instead of a single point focus, giving an image that is ghosted, flared or appears doubled and distorted.

It does not cause blindness as such, but can lead to disabling vision loss.

Probably both genetic and environmental causes

The cause of keratoconus remains unknown, although recent research seems to indicate that it may result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Some cases of keratoconus have a hereditary component and studies indicate that about 20% of keratoconus patients have affected relatives. If there is no evidence of keratoconus in successive generations of a family, there is less than a 1 in 10 chance of the children of a person with keratoconus also having the condition.

Other genetic diseases are associated with keratoconus, including Trisomy 21 (Down's Syndrome), Marfan's Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Some studies point to keratoconic corneas lacking structural fibris that maintain the stability of the cornea, leading to a thinning and weakening of the cornea.

Oxidative stress may also be linked to the development of keratoconus. Under this theory, keratoconic corneas are unable to eliminate free radicals and self repair resulting structural damage like a normal cornea. This weakens the bonds in the cornea.

Avoid eye rubbing

Keratoconus is often associated with atopic diseases (hayfever, eczema, allergies, asthma etc) which can result in people having itchy eyes.

Keratoconus is often associated with atopic diseases (hayfever, eczema, allergies, asthma etc) which can result in people having itchy eyes.

Excessive and vigorous eye rubbing can break down the fibres of the cornea and has therefore been implicated as a causative factor or a trigger to progressive keratoconus in persons having a genetic disposition to the disease.

Download a flyer on eye rubbing and how and why you should stop it

Diagnosis

Keratoconus can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages as the initial symptoms can be associated with other eye conditions. A telltale sign as the disease advances is frequent changes in spectacle prescriptions and increasing complaints from the patient about their corrected vision.

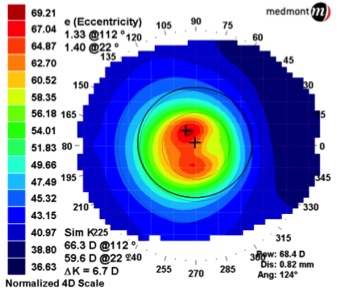

Keratoconus is usually diagnosed with a corneal topography, an ophthalmoscope, a retinoscope or a slit-lamp examination. The corneal topographer is the best instrument for detecting early keratoconus as it creates a computer-generated colored topographical map of the cornea that highlights the development of a cone.

Keratoconus is usually diagnosed with a corneal topography, an ophthalmoscope, a retinoscope or a slit-lamp examination. The corneal topographer is the best instrument for detecting early keratoconus as it creates a computer-generated colored topographical map of the cornea that highlights the development of a cone.

Other signs of keratoconus identifiable in an eye examination include:

- Thinning of the cornea from its normal thickness of around 550 microns

- Fleischer's ring (an iron colored ring surrounding the cone)

- Vogt's striae (stress lines caused by corneal thinning)

- Apical scarring (scarring at the apex of the cone)

Measurements of corneal thickness are also useful for diagnosis. Corneal ultrasound or pachymetry can accurately measure the corneal thickness and can detect thinning that occurs in keratoconus. Normal corneal thickness is approximately 0.55mm (or about the thickness of a credit card).

Corneal Tomography is another method of measuring corneal shape and corneal thickness. This technique measures the front corneal surface and the inside corneal surface and so provides a comprehensive measure of corneal thickness across the whole surface.

Corneal topography, corneal tomography and corneal ultrasound are simple, quick and painless.

Most patients with early keratoconus will not have any obvious corneal signs, substantial corneal thinning or significant spectacle corrections. Accurate and reliable corneal topography or corneal tomography are the best methods for detecting any changes of the corneal shape. This will allow an appropriate assessment of each patient to determine which patients had significant progression and so need to be referred for consideration of corneal cross-linking (CXL).

Fairly common

Keratoconus was estimated to occur in at least 1 out of every 2000 persons in the general population based on studies done in the early 1980s. However better screening techniques indicate that it may be as high as 1 in 750 persons worldwide (Hashemi H, et al. Cornea. 2020). A recent Australian study published in 2020 indicates a prevalence of 1 in 84 amongst 20 year olds. (Chan E, et al. Ophthalmology. 2020). The higher prevalence of keratoconus indicated by recent studies probably reflects better diagnostic techniques rather than a rising incidence of keratoconus.

Greater awareness of the systemic associations and risk factors related to the development of keratoconus, including asthma, atopic diseases leading to chronic eye rubbing, connective tissue disease, long-term gas-permeable contact lens wear, sleep apnea and Down syndrome has also improved diagnosis by eye-carers.

There appears to be no significant preponderance with regards to either men or women although due to genetic factors, it seems to have a higher occurrence rate in certain populations.

Signs and symptoms

The initial symptoms of keratoconus are usually a blurring and distortion of vision that may be corrected with spectacles or soft contact lenses in the early stages of the condition.

The initial symptoms of keratoconus are usually a blurring and distortion of vision that may be corrected with spectacles or soft contact lenses in the early stages of the condition.- Frequent changes to the spectacle correction may be required as the cornea becomes progressively thinner.

- As the disease progresses, a patient will suffer increased blurring and shortsightedness,

- light sensitivity,

- halos and flaring around light sources that can make night driving difficult

- Double and /or multiple images with monocular viewing

Other symptoms experienced by people with keratoconus (but which are not directly related to the disease itself) include:

- Eye strain, squinting, headaches and general eye pain

- Dry eyes, irritated eyes, itchy eye, allergies

- Excessive eye rubbing

A young person's disease

The onset of keratoconus can be anywhere between the ages of 8 and 45. In the majority of cases, it becomes apparent between the ages of 16 and 30 years.

Keratoconus tends to be more aggressive when diagnosed in adolescence.

Progression usually continues until the age of about 40 years.

Because it affects people from puberty onward, it can have a significant impact on a person's education, work, social and family life if not treated correctly.

Both eyes affected

Keratoconus generally affects both eyes. Even though keratoconus is basically a bilateral condition, the degree of progression for the two eyes is often unequal; indeed, it is not unusual for the keratoconus to be significantly more advanced in one eye.

Studies show that keratoconus occurs in one eye only in a very small percentage of cases (<1%) - and in those cases keratoconus may be present in the other eye but undetectable.